Neurotic perfectionism in gifted individuals

Dr. Hamed Al-Sahou

Talent

29

Contemporary societies strive to support and develop the skills of gifted individuals. Nurturing outstanding individuals and developing their capabilities is a successful investment that contributes to achieving sustainability and developing society. The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, represented by the “King Abdulaziz and His Companions Foundation for Giftedness and Creativity”, plays a prominent role in enhancing these efforts through its uniqueness in developing the minds of young people and harnessing their creative talents. The Foundation has paid great attention to understanding the characteristics of gifted students in order to provide distinguished educational services and reduce the obstacles they may face during their educational journey.

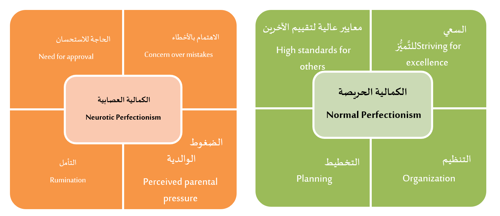

On the other hand, others insist that perfectionism is an adaptive trait acquired due to the talent being affected by upbringing factors and surrounding variables that either enhance or inhibit the individual's desire to achieve perfection in his work. The proponents of this view rely on a number of evidence and clues extracted from various studies that prove that perfectionism is an acquired trait and not a fixed trait; an individual who has a tendency towards perfectionism is in some areas such as study, work, home, clothing, relationships, or others. But not all of them at the same time. If it were a personality trait, the individual would have to be perfect in everything, as it is considered a rare case (Stoeber, 2018). Secondly, evidence indicates that perfectionism is linked to previous reinforcing experiences that the individual was exposed to during family upbringing, especially in the early stages of development (Flett, et al., 2002). Longitudinal studies have also shown that perfectionism is variable and not fixed, with some finding that there are changes in the level of perfectionism in individuals over time (Stoeber, 2018). However, criticism has extended to this controversy and discussion. For example, Frank and Gaudreau tried in their study to bridge the gap between the two schools, as they concluded that perfectionism is a multi-level trait or characteristic at the level of people among themselves and at the level of the individual between himself and himself, influenced by internal and external factors (Franche & Gaudreau, 2016).

Conclusion

References

Al-Sahou, Hamed, Al-Ajmi, Mohammed, and Al-Anzi, Salama. (2023). The relationship between neurotic and anxious perfectionism and self-assertion among academically outstanding students in the twelfth grade in the State of Kuwait, Journal of Educational Studies and Research, 3(8), 201-237

Chan, D. (2009). Perfectionism and goal orientations among Chinese gifted students in Hong Kong. Roper Review, 31(1), 9-17

Hill, R., Huelsmann, T., Fur, R., Killer, J., Vicente, B., & Kennedy, C. (2004). A New Measure of Perfectionism: The Perfectionism Inventory. Journal of Personality Assessment, 82(1), 80-91

Did you benefit from the information provided on this page?

visitors liked this page